Monday, February 15

6:22 AM The main takeaway I got from reading Galatians over the weekend? It’s much easier to be saved than to act saved. It takes very little effort to sound spiritual. But being spiritual? That’s another story. And just what does a saved person sound like? Well, there’s Tommy Theologian — you know, the guy who’s always talking about Calvinism and expository preaching and historic premillennialism and agape love. Being saved is all about what you know. John Stott used to call people like this “tadpoles” — all head and very little body. Then there’s Pat Popular, with his “Praise Gawd” outbursts and holy “Amens!” In Galatians 5-6, Paul offers us a better definition of “saved.” He is adamant that Christians show their faith by good (and not evil) living. His list of vices in 5:19-21 is hardly arbitrary. You can see this in my translation:

The opposite is also true: Paul’s nine-fold “fruit of the Spirit” goes from descriptions of the mind to human relationships to principles that guide one’s conduct. The word “love” controls it all. At some point, we need to unplug from today’s propaganda machine that bombards us with the three-letter word “Get!” It is the nature of God to give rather than get. And born-again Christians share that nature. But is the life Paul is describing really possible? He seemed to think so. That’s what grace is all about. We have received the opposite of what we deserved. Now it’s our turn to pass that grace on to others. We do this through love.

What is love? Read 1 Cor. 13. Or Rom. 12:9-21. Or Gal. 5:22-23. Then try writing a few practical applications of your own. For example, you might say, “Love is the kindness my son showed me when I needed my tractor fixed.” Or, “Love is the kindness I showed when I brought him and his family lunch the other day.” Love is ______. You fill in the blank. On a day-to-day basis, I’m more struck by the little deeds I see in others than their intellectual prowess or their spiritual boisterousness. When I look in the mirror each morning, I think, “Lord, you actually love this person.” Indeed he does. He’s got big dreams for me. For you as well. And he can spot a cover-up a mile away.

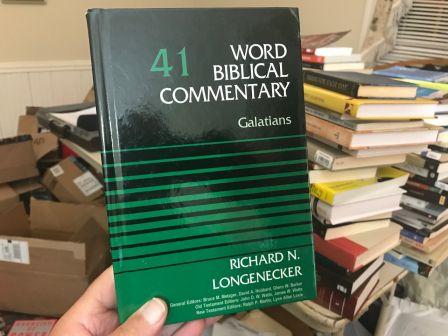

P.S. You may have noticed in my rendering of Gal. 5:19-21 the couplet “envious and murderous.” The word “murderous” isn’t found in some Greek manuscripts. I’ve argued for its originality here.

This, to me, is a clear-cut case of an accidental omission due to a mistake of the eye. Alas, the Alexandrian Priority position is so entrenched in New Testament studies today that scarcely any attention is paid to the longer reading. My friend Keith Elliott used to call this “The hypnotic effect of Aleph and B.” I’m glad to know I’m not the only one concerned about that. I guess that’s why I write books and compose essays and produce power points on the subject of textual criticism. The only way to know for sure whether or not “murderous” is original to examine the evidence for yourself.

(From Dave Black Online. Used by permission.)