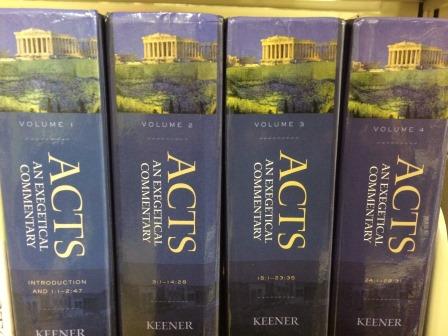

One article in particular caught my eye. In the latest issue of Trinity Journal, Stan Porter asks (in essence), “Whatever happed to brevity?” His essay is titled, “Big Enough Is Big Enough.” He’s reviewing Craig Keener’s monumental 4-volume commentary on Acts (Baker).

Porter seems to think that commentators should stick “closer to the Greek text” than Keener has (p. 45). In addition, Keener’s work, at 4,640 pages, is deemed too comprehensive in scope – what Porter calls “mission creep” (p. 35). Porter also seems to think that commentaries should be primarily exegetical in nature. “Scholars who have innovative ideas about related historical, theological, and other issues – and I hope that there are still some who do – should use monographs and journal articles for such major and significant contributions” (p. 45).

Porter seems to think that commentators should stick “closer to the Greek text” than Keener has (p. 45). In addition, Keener’s work, at 4,640 pages, is deemed too comprehensive in scope – what Porter calls “mission creep” (p. 35). Porter also seems to think that commentaries should be primarily exegetical in nature. “Scholars who have innovative ideas about related historical, theological, and other issues – and I hope that there are still some who do – should use monographs and journal articles for such major and significant contributions” (p. 45).

There’s a lot of truth to what Porter is saying here – at least when it comes to book size. Robert Louis Stevenson once said, “The only art is to omit.” If it’s a choice between succinctness and verbosity, I’ll take the aphorist any day. “Bigger is better” may be a mantra among church planters and pastors, but too many writers seem to be afflicted by the disease of gigantism. Today’s writers bore on for far too long – including me (my book The New Testament: Its Background and Message tops out at a whopping 672 pages). So I’m not sure that Keener is the only one guilty of overwriting. In the menagerie of overweight books, one could perhaps include the most recently published “beginning” Greek grammars, including Porter’s Fundamentals of New Testament Greek, which consists of 492 pages. Rod Decker’s has even more: 704. Note that these are self-styled beginning grammars. Part of the problem is what I call “Got-To-Say-Everything-I-Know-About-the-Subject-Itis.” The result is often three books in one: a beginning grammar, an intermediate grammar, and a textbook on either textual criticism or linguistics. Keener, of course, is keenly aware of the breadth of his 4-volume commentary. In his own defense he writes (vol. 1, p. xv):

Had I put this material instead into 350 nonoverlapping twenty-page articles or 35 two-hundred-page monographs (with at least one on each chapter of Acts), this research might have sold more copies but cost readers many times more.

This statement is almost prescient: Keener seems to be anticipating Porter’s suggestion that scholars “use monographs and journal articles for such major and significant contributions.” Keener also directly addresses the issue of length when he writes (p. xv):

… I have preferred to provide this material as thoroughly as possible as a single work, and I owe my publisher an immense debt of gratitude for accepting this work at its full length.

That Keener combines exegetical insights with observations about theology, history, etc., should not surprise us. Keener is a self-confessed “generalist scholar” (p. 4, note 2) who grapples not only with the text but with sociohistorical questions as well. As he explains (p. 5), “While seeking to provide a commentary of some general value, I have concentrated on areas where I believe my own researcher’s contributions will be most useful.” His work therefore “…does not focus as much attention on lexical or grammatical details (a matter treated adequately by a number of other works).” In short, Keener views his work as “sociorhetorical” (p. 25), pure and simple. I therefore fail to see how one can fault him for not being “exegetical” enough when he himself makes it clear that he doesn’t deal simply with Greek exegesis. In short, I agree with N. T. Wright:

With this enormous commentary, Craig Keener deploys his breathtaking knowledge of the classical world to shine a bright light on both the big picture of Acts and ten thousand small details. Students of Acts will be in his debt for generations to come.

I for one have benefited greatly from Keener’s insights into the text of Acts. It’s one of the first commentaries I turn to whenever I need help in interpreting Luke’s history of the church. Keener does a fantastic job of explaining the text in a way that’s easy to understand. Used alongside the “Four Bs” (Barrett, Bock, Bruce, and Ben [Witherington]), I think you’ll find Keener’s work to be a rich source of information about Acts. Sociorhetorical analysis is Keener’s area of specialty and it shows. You would have to buy several commentaries on Acts to cover this much ground. Also worth noting is the fact that both Jimmy Dunn and Richard Bauckham have endorsed this commentary. Indeed, so did Stan Porter (at the Amazon site):

Early Christianity developed in a complex and multifaceted context, one that Craig Keener masterfully presents in this socially and historically oriented commentary on Acts. As one has come to expect from Keener, there is thorough knowledge and use of the best and most important secondary literature and abundant utilization of a wide range of ancient sources. This is a commentary that will continue to serve as a detailed resource for both scholars and students.

I can’t recommend Keener’s works enough. That goes for all of his books. Ditto for Stan Porter. His books are always extremely well-researched. We might disagree in terms of Greek pedagogy (there’s much to be said for brevity), but when grammatical issues arise, Porter’s voice is always a good one to take into account.

(From Dave Black Online. Used by Permission. Nov. 16, 2016.)