( March 22, 2019) 7:45 AM “As iron sharpens iron, so one person sharpens another” (Prov. 27:17). This verse might well be the motto for our upcoming Linguistics and New Testament Greek conference. I realize that in its original context this proverb is about individuals. But it’s also true, I believe, about biblical exegesis and linguistics. Each method is a challenge to the other, for better or for worse. Simply put, there seems to be a strong correlation between the Bible and science, between Greek and linguistics. During the so-called Enlightenment, many abandoned the Bible for science altogether. But in recent years, the Bible and science have moved closer together. It became apparent that Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic were, in fact, languages just like any other human languages, even though God had used them to inscripturate His divine truth. If it is true that Koine Greek is a language, then the science of linguistics has much to commend it. The main alternative — viewing the Greek of the New Testament as sui generis, as a kind of Holy Ghost language — has in my opinion little evidence for it compared with biblical linguistics.

In the past several decades, the study of New Testament Greek has moved from viewing Greek as a special field of study to viewing it as a part of the broader science of how languages work. The shift began well before I published my book Linguistics for Students of New Testament Greek in 1988. It was essentially based on the groundbreaking work of 19th- and early 20th century scholars such as Moulton, Blass, Winer, and A. T. Robertson. Since then, biblical scholars have split over whether or not exegesis allows for the full integration of linguistics into biblical studies. Some evangelicals have felt threatened by this new approach to the study of the Greek of the New Testament. However, since we evangelicals believe that God is the unifier of the cosmos, we shouldn’t feel threatened by the various models of linguistic research that have become available over the past century. Among the branches of linguistics, historical-comparative linguistics proved to be the most interesting to biblical scholars of the past century. Robertson’s A Grammar of the Greek New Testament in the Light of Historical Research — affectionately known to students as his “Big Grammar” — moved biblical studies in this direction like no other work that preceded it. Then discoveries in the field of semantics began to inform our discipline, resulting in groundbreaking works like Moisés Silva’s Biblical Words and Their Meanings and Johannes Louw’s Semantics of New Testament Greek. Currently it looks like the field has begun to burgeon far beyond anyone’s wildest imaginations, owing in large part to the tireless work of scholars like Stan Porter, Steve Runge, and Stephen Levinsohn. If we take semantics as a trustworthy approach, books like Biblical Words and Their Meaning become indispensable. Clearly our discipline could do without such exegetical fallacies as illegitimate totality transfer, etymologizing, and anachronism. With the rise of the field of biblical linguistics, evidence that the Greek of the New Testament is in fact not sui generis has risen dramatically, putting even more pressure on the claim that the New Testament is comprised of Holy Ghost Greek.

With this brief summary, we see that the field of New Testament Greek linguistics has made a number of discoveries that challenge evangelicals’ traditional approach to hermeneutics. It has also made others that challenge the methodological certainty of the scientific community. Unfortunately, evangelicals have not found as much common ground as we would like for a unified response to modern linguistic science. Yet all can (and do) agree that the Bible is God’s inspired Word, and that it is crucial that people recognize this. However, there is as of yet no agreement on the detailed model of linguistics that should prevail in our schools and seminaries. How is New Testament Greek to be pronounced? How many aspects are there in the Greek verb system (two or three) and what should we call them? Is the term deponency to be used any more? What is the unmarked word order in Koine Greek? These are basic and central matters that should not be overlooked in the midst of our intramural disputes.

The speakers at our conference hardly agree among themselves on many of these topics. We should not be surprised to find such disagreement. After all, evangelicals are not united in many other areas of interpretation, including the mode of baptism, the biblical form of church government, eschatology, and whether or not miraculous gifts are valid today. Despite our disagreements, however, we should not throw in the towel but should continue to seek solutions in all of these areas. In our conference, we hope that the papers will give us some helpful suggestions for making progress in relating the New Testament to the science of linguistics. For an evangelical, both nature and Scripture are sources of information about God. But because both have fallible human interpreters, we often fail to see what is there. Ideally, scientists (whether secular or evangelical) should favor the data over their pet theories. Hence we have asked each of our speakers to be as fair and judicious in the way they handle disagreements in their assigned subjects.

Many pastors and even New Testament professors in our schools do not think they are exegeting God’s revelation in nature when they do exegesis. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t. This is not to say that New Testament Greek linguistics has solved all the problems of relating biblical and scientific data. It has not. Further investigation and reflection, long after this conference is over, will be needed in this area. Our desire in organizing this conference is that, far from treating science as an enemy, we should all realize that science is simply the process of studying general revelation. Our hope is that God will continue to reveal Himself to us as long as we do not rule out divine inspiration in the process.

Linguistics is, of course, a large subject. No one can ever hope to master its entire scope. Nevertheless, it is obvious that students of New Testament Greek can and should have a working knowledge of linguistics – the science of language.

One thing seems clear as we anticipate our conference. We who study and teach New Testament Greek cannot be satisfied with superficial answers. We must carefully scrutinize the pages of general revelation and consider how they may influence our current approach to Greek exegesis. If we need to be cautious in our handling of the scientific data, we also need to be hopeful and optimistic.

(From Dave Black Online. Used by Permission.

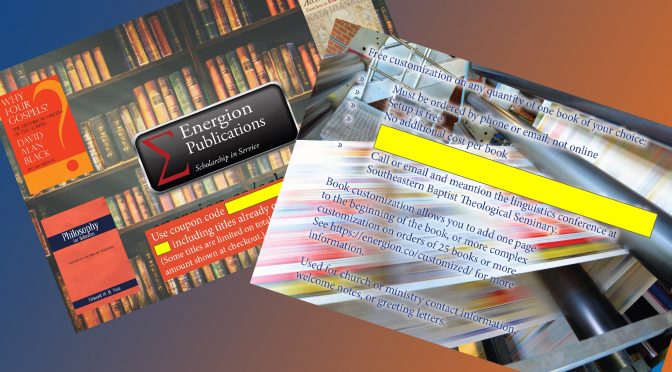

Note on header: Energion Publications will have a 4×6 handout card with special offers for conference attendees. You won’t want to miss either the conference or these offers!)